February 9, 2021

Back To Running the Open Table

There’s a tendency for people to look back upon histories and apply anachronistic labels or methods upon them. (Ever notice that every ancient/fantasy accent is British?) Likewise, when we think of the first roleplaying groups, we tend to think about our own experiences, tacking our modern expectations onto the past.

While this is a somewhat natural inclination, I think it’s worth placing these aside for a moment and put these games in their proper context. It can help shed a little light on why certain norms have risen and faded, and why we look back on some early practices and scratch our heads.

Much of what we’ll be reviewing is focused on D&D, but it serves as an analogue to what much of the hobby was up to at the time, given its dominance in the market.

HOMEBREWED SETTINGS

When early gamers first started to venture into this whole roleplaying thing, they weren’t given a ton of options for setting. Or at least not from publishers.

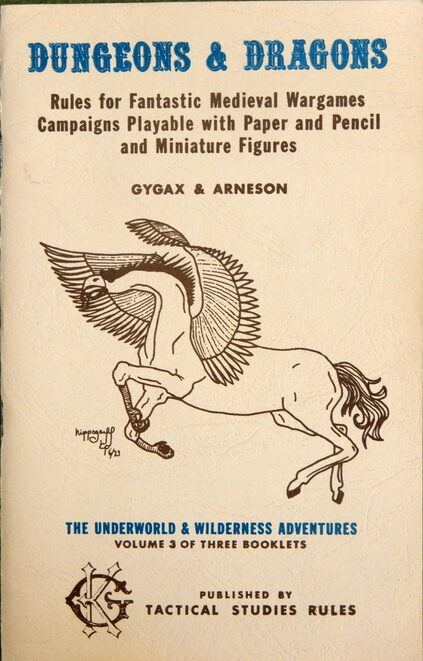

There were various flavors. There was the ambiguous fantasy world of early D&D and the many variants that soon propped up. For those who desired a richer setting, there was the highly defined world of Tekumel in Empire of the Petal Throne. But with theexception of EPT, most of these games were undefined and setting devoid. Many designers expected (and in fact, encouraged) GMs to build settings out of whole cloth.

Most would do exactly that, creating varied and unique landscapes, unified among other play groups by only their rules and structures. (You could expect just about any swords and sorcery game to have a dungeon.) Homebrewed scenarios weren’t so much the norm as much as they were the sole option.

And within that, player would often find themselves neck-deep in a world rife with opportunity.

The lack of setting and prepackaged material meant that players and GMs had to participate in building the setting. The PCs often had just as much a role in changing the world as the GM. (By that, I don’t mean that they were literally taking the GMs worldmap and adding new dungeons to it. I mean instead that they were constructing new encampments or building baronies within the existing world. They were looking at the game and staking their claim in it.)

Many groups would have multiple domains ruled BY players. Within them, players could create their own cultural norms and practices. And then there would be other PCs who lived within those kingdoms that would do the typical dungeoncrawling, hoping to become powerful enough to one day rule their own domain.

And to top it off, OD&D HAD RULES on how players could go about domain-level play. I believe that the mere existence of these rules made them a viable goal and active part of play.

THE LONG HAUL

Of course, getting to the point where you are powerful enough to own anything beyond the equipment in your pack can be trying. How were these players able to get to the point where they were ruling whole kingdoms or realms? How were players able to so deeply integrate themselves into the worlds, rather than just wandering vagabonds moving across lands in the quest for power?

The answer is time.

Even by the time of D&D’s 1974 release, Gygax, Arneson and others had already been running campaigns for several years. And many of the games that were started shortly after its release continued well through the 70’s and on. Most of these ended up transitioning into AD&D, but the campaigns continued all the same. At that time, a short campaign seemed to be considered a few months or so. And these shorter games weren’t considered the norm.

By comparison, modern conventions consider a long campaign somewhere between 10-20 sessions, played out over the course of 4-8 months. To be completely fair, that is certainly a sizable chunk of time to place into a game, and I want to make clear that I’m not claiming this is a “one true way” to play. There’s certainly merit to single-arc campaigns and one-shots which don’t have to take up large chunks of your lifespan.

But I do think there is something to be said about the depth and verisimilitude that can only really come from a campaign that has the history to back it up.

It’s one thing to fabricate an entire timeline, stretching back centuries or longer, to give the world some color and purpose. It’s an entirely different thing to have actual years built off of the that, where PCs have become legends (or maybe even gods), evil empires have risen and fallen, and many arcs have passed. That kind of play almost never happens anymore.

On top of that, most groups weren’t playing two or three sessions a month. Many anecdotal accounts indicate that players were meeting up several times a week! (Of course, a lot of these groups were doing open-table gaming, which made this much easier to achieve.)

When your game is one that has the strength of multiple years of worldbuilding behind it, it’s no surprise players would be interested in coming back week after week to play.

A PLETHORA OF CHOICE

This of course, brings us to another point, somewhat related to the piece about homebrews. Even more than a lack of published settings, there just weren’t a lot of games to choose from.

Sure there were a lot of different fantasy games. But to some extent, nearly all of these were fan-hacks of OD&D. Games like Runequest and Tunnels & Trolls were among the more ambitious edits of the bunch, but were still D&D-esque in concept. Even then, most groups usually picked a variant they preferred, and stuck with it.

It wasn’t until designers starting introducing radically different game structures that the broader scope of games being played took hold.

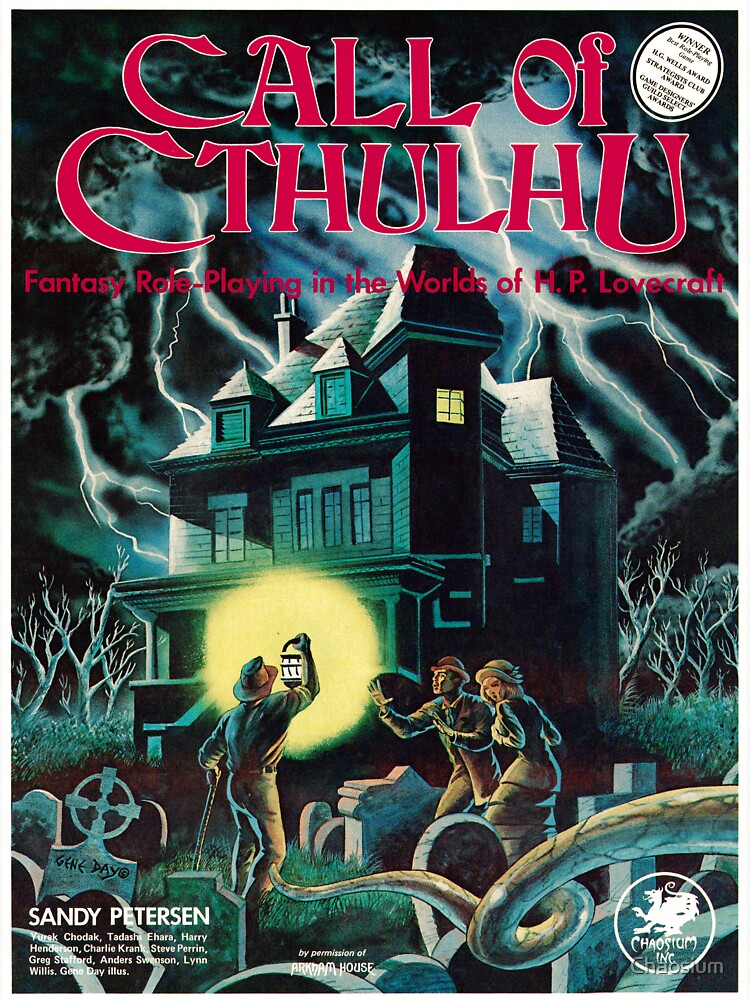

A great example of this is Call of Cthulhu. By the early 80s, the whole dungeon/hexcrawling thing was getting a little dull for players. Many had transitioned to AD&D and the supported modules for the game weren’t encouraging domain-level play. The result was a sort-of leveling out, where players would grow tired of simply traveling the overworld, taking on dungeons and threats increasingly weak when compared to the PCs.

What a game like CoC offered wasn’t simply a new genre-bust for the hobby (although it certainly was that.) It gave players and GMs alike to try something totally new- mystery and horror structures.

By shifting the prevailing game structure on its head, making players increasingly powerless rather than powerful, it opened the doors to some of the more innovative designs of the period.

And with this variety in design, and an understandable desire to try them all, it became quite difficult to try and participate in that years-long campaign multiple times a week.

Compare that to today’s gamers, by way of looking at my own game schedule. I have my OD&D Open Table, a more typical campaign I’m planning for a homebrew system, and an ever-growing list of other games I plan to run sometime in the next year or so. Additionally I play a fair number of low/no-prep games like Fiasco or Technoir. Pretty quickly it becomes easy to see why it’s difficult to choose ONE game to devote all my time to.

And maybe that’s just me. I really could just be a really small minority of gamers who try to play as many games as possible. But I really don’t think that’s the case.

Once you get outside the group of players who are only playing D&D, most gamers play a lot of different games.

The earliest groups didn’t have the plethora of choices that we do for play. Now, we choose to play space opera sci-fi one night, cosmic horror the next, and some one-shots for a cyberpunk and low fantasy game next week. There’s so many opportunities to play new games that there’s rarely a group who is willing to participate in building a world in the way these early players would. It’s no surprise that the linear adventures of 2nd edition arose in the 80s, because there was so much competition from other games that players were rarely spending years and years exploring one setting.

CONCLUSION

I may have babbled on about my own interpretations of history and made some bold assumptions about the way games are played. But I think there’s some value to doing that. One of the reasons I’m writing this series is to reflect on the hobby’s origins and how much it has changed from those early days.

From the years long OD&D games (some of which are still ongoing!) to the solo journals and micro-RPGs being developed in game jams and by indie designers, there’s a ton of differences between them in purpose, style and structure. But there’s also a commonality that brings a lot of this together. When we all sit down to play, we’re still looking to explore worlds of wonder, just like the early gamers were doing years ago.

Back to Running the Open Table